“Crowdsourcing is the process by which the power of the many can be leveraged to accomplish feats that were once the province of a specialised few.” – Jeff Howe

On the Internet today, we see an awful lot of things with the word “crowd” in front of them. It makes sense – after all, the Internet is about bringing vast amounts of people together from all around the world to make new things possible. The most exciting thing about being online is seeing what innovative results can come from combining those people with the wonders of technology and a few ingenious ideas.

The word crowdsourcing itself is very much a product of the Internet age, as it was coined by Jeff Howe in a 2006 Wired magazine article, ‘The Rise of Crowdsourcing’, and later given a more refined definition in his blog. You could argue that each of the terms I discuss in this blog post is just a variant form of crowdsourcing, but I think they warrant being considered separately, because by and large they’ve evolved beyond the point where they fit Howe’s definition at the top there, and instead have taken on a life and characteristics of their own.

Putting the Crowds to Work

A great example of crowdsourcing to elegantly solve a complex issue is the way that Facebook, in its early days, translated its interface into various languages. Users could submit their own translations for different phrases – like “to poke” – and vote on which translation they thought was best, saving Facebook’s developers untold amounts of money and time that would otherwise have been spent on professional translations. Google Translate learns and improves the accuracy of its translations through much the same means.

A more recent and light-hearted example of a crowdsourced venture is Fifty Shades of Green, in which members of the review channels Channel Awesome and Chez Apocalypse created a Twilight-esque parody novel with Cthulu in place of vampires. They crowdsourced everything from the characters’ names to the actual writing of the novel, giving video updates about each stage of the project and offering insights into the world of Young Adult paranormal romance. The crowdsourcing format allowed Fifty Shades of Green to combine its creators’ critical talents with the imagination and humour of its audience, as well as giving them the chance to feel involved and more personally invested in the project.

The Knowledge of Crowds

Then there’s crowdwisdom, the name sometimes given to projects that thrive on the collective knowledge of a crowd of people. The most obvious example of crowdwisdom is of course Wikipedia, which uses the collective wisdom of a well-over-20-million-strong crowd (and no matter what sceptics try to argue, it is accurate). When the English-language version took itself offline for just 24 hours in protest of the Stop Online Piracy and Protect IP Acts, it triggered widespread panic and caused a hashtag with thousands of ludicrous facts to trend on Twitter. Countless other sites across the Internet make use of a Wiki format, from TVTropes to Encyclopedia Dramatica, and you’d be hard pushed to find a fandom that doesn’t have its own Wiki made up of the detailed knowledge of its fans about every aspect of its universe. Yahoo Answers is another indispensable source of crowdwisdom, and you could easily argue that many types of discussion forum classify as crowdwisdom too.

As an aside, of all the terms that I mention in this post, “crowdwisdom” is the only one that doesn’t yet double as a verb. You can say “I crowdsourced it”, “I crowdfunded it” and “We crowdplayed it” (no-one really does yet, but it doesn’t sound grammatically wrong) but you wouldn’t say “I crowdwised it” or “I crowdwisdomed it”.

Monetising the Crowds

Crowdfunding has had a lot written about it of late as more and more people are catching on to its incredible capacity to influence the future direction of the creative industries, and as bigger and bigger names are making use of it to realise their own projects. Wired ran an article last month about the impact that the crowdfunding site Kickstarter has had on indie filmmaking. Yahtzee, the fast-talking games critic behind Zero Punctuation, recently complained that crowdfunding was keeping games development stuck in a rut as, when the masses are given the power to decide which gaming projects receive funding, they are more likely to support something familiar and nostalgic than something new that they can’t be sure they’ll definitely enjoy (the “nostalgia factor”).

Whatever its unfortunate side-effects might be, though, no-one can deny the potential of crowdfunding to realise projects that would have had great difficulty being taken seriously enough to secure funding by traditional means. Earlier this month, the first ever web series adaptation of a fanfiction, A Finger Slip, reached its funding goal on Kickstarter, which is a massive development for the world of fandom and the idea of fanworks being seen as legitimate works of art.

Gaming with the Crowd

Crowdplaying isn’t a new concept, but the idea has been receiving attention like never before as for the past week and a half, the web has been buzzing with updates, jokes and news about Twitch Plays Pokémon. TPP is a livestream of an emulator playing the first-generation Pokémon GameBoy game Pokémon Red/Blue, but with a bot controlling the game which responds to commands inputted in the stream chat. Its anonymous creator thought the idea of a collaborative attempt to complete a game would be entertaining, but was unprepared for the enormous popularity of the idea.

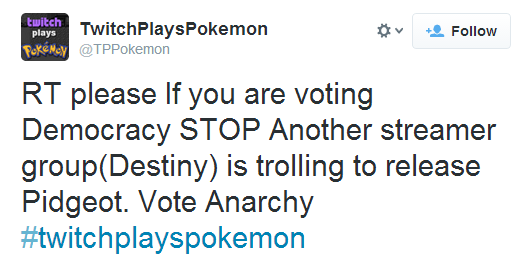

The game’s protagonist has progressed surprisingly far considering the predictable chaos created by contradicting commands and attempts by trolls to hinder the progress of the game. At one point the creator was forced to implement an Anarchy/Democracy slider, which responded to votes in the chat for “anarchy” or “democracy”. Democracy Mode attempts to systematically tally up the votes for a particular course of action over a span of 20 seconds, selecting the most popular action every 20 seconds and then resetting, whilst Anarchy Mode (the game’s original setup) simply selects chat commands at random. Democracy Mode enabled the players to successfully navigate the Safari Zone (which with a limited number of steps and Pokéballs requires very careful decisions about what to do and where to go), but it was recently discovered that Democracy mode might be even more vulnerable than Anarchy to mean-spirited trolling:

Twitch Plays Pokémon has generally been viewed as a social experiment, although personally, I don’t think it reveals anything that we didn’t already know about the capacity of a crowd of Internet users for chaos, trolling, and a worshipful fixation on random objects and concepts. With that said, this honestly philosophical insight into the meaning and attraction of TPP’s Anarchy mode by Reddit user duxknight made me rethink my dismissal of the game as immature viral fun. Even so, I’m more interested in what this new incarnation of crowdplaying might mean for gaming. Needless to say, TPP has spawned spin-off channels, such as Twitch Players, which is working its way through Pokémon Crystal without the benefit of an Anarchy/Democracy slider, and Twitch Plays Super Mario Bros, another classic Nintendo game which is now being crowdplayed. (The nostalgia factor is strong in the choice of games here, too).

Crowdplaying isn’t about to revolutionise the way games are played, but it does open up some interesting possibilities for the future. I’m thinking there’s potential for a charity event in the style of Awesome Games Done Quick, where instead of speed-runs, people can choose a selection of games to be crowdplayed, and donate money to take part in the fun. The Twitch Players stream has already implemented a donation button, although it’s unclear where the money is actually going given that Twitch is a free-to-use service. Crowdplaying could also become a new form of Let’s Play, featuring well-known gamers trying to work together to play through a game with amusing results.

For now, it remains to be seen whether the original Twitch Plays Pokémon can successfully complete the game or whether trolls will undo all its hard-won progress. If the stream were to dissipate, would its imitators die off too, or will this new variant of crowdplaying stick around and evolve further? Let’s wait and see what happens.

Leave a comment